Pelicans' longer visits baffle expertsBirds usually fly south when it’s breeding time, but are lingering this year

By CASSANDRA PROFITA

The Daily Astorian

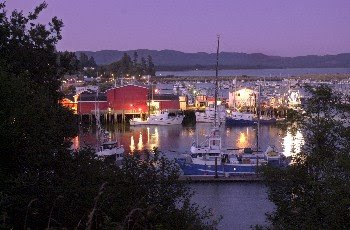

This winter, bird watchers have spotted thousands of brown pelicans roosting on the North Coast about a month after they traditionally head south.

Experts aren't sure why they're still here so late in the season, but they suspect it's because the coast hasn't seen as many wild winter storms so far this year.

The California brown pelicans are endangered but could be de-listed soon, as their populations have rebounded dramatically since the pesticide DDT - which thinned the birds' egg shells and prevented successful breeding - was banned in 1972.

Researchers at Oregon State University counted a record high of more than 12,000 pelicans on East Sand Island in the Columbia River estuary in September. The first birds move north to Oregon and Washington in April, and many more migrate throughout the summer before their numbers peak in August through October.

But normally the last of the pelicans have returned to southern California and Mexico to breed by mid-November, said Astoria resident Deborah Jaques, a wildlife biologist for the consulting firm Pacific Eco Logic.

Jaques, who has been studying the endangered pelicans for 20 years, was stunned to find more than 5,000 pelicans at East Sand Island, the largest communal roost for pelicans in the Northwest, on Nov. 24.

"This is unprecedented," she said. "We've never seen anything like this before, where it's so obvious there's so many."

She even saw some birds that had already begun changing colors in preparation for the breeding season. When they're getting ready to breed, the plumage on the pelicans' heads turns white with a yellow crown and their gular pouch, the soft underside of their beak, turns red.

"Usually they're gone before they start turning colors," said Jaques.

Lisa Sheffield-Guy, a seabird biologist and director of the Haystack Rock Awareness Program, said she couldn't help but count the flock she saw near Cannon Beach at the end of November.

"I counted up to 4,000 at one point," she said. "And that was just at the mouth of Ecola Creek, on the north side of Bird Rocks. I'd say they're about a month late this year."

All along the coast

All along the coastRoy Lowe, project leader for the Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex, said he's been getting reports on the wintering pelicans from all along the coast. In a recent aerial flight along the coast from the California border to Seaside, he saw pelicans along the entire route.

"It's pretty late in the year for this many pelicans to be around," he said. "It was notable that we were seeing them all the way along. It was a pretty amazing sight."

His survey from California to Washington revealed the highest pelican count ever - 17,000. In 1988, the same survey counted just 4,800 pelicans.

"The birds are doing really well," he said. "Why they're staying so late is sort of the mystery. ... We're hoping they move soon because we're concerned some big powerful storms could come in and cause some mortality of the birds."

One of the reasons the pelicans might be staying, bird experts agreed, is that there is still plenty of forage fish such as anchovies for them to eat.

Jen Zamon, a marine ecologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Point Adams Lab in Hammond, said mild fall weather and its effect on the ocean could be playing a role.

"The surface of the ocean can really be affected by bad weather," she said. "If the surface water is really turbulent with big seas and crashing waves, the fish won't be at the surface. They'll go to where it's less turbulent, which means they become out of reach to the pelicans. Pelicans can only dive so deep. If there's nothing for birds to eat, they'll start heading south."

Jaques wrote her master's degree thesis on the expansion of the brown pelicans' range and possible ties to climate change in the mid-1980s.

She found the pelicans were abundant in Oregon and Washington in the 1800s, but their range shrank to the south around the turn of the century - long before DDT caused their numbers to crash.

Since their population has begun to rebound, the pelicans' range has expanded once again, but the expansion also corresponds with a warming cycle in the northern Pacific Ocean, Jaques said.

Coming here soonerThe birds appear to be coming to Oregon and Washington earlier in the year and staying later through the winter, she said, which makes her wonder whether it is part of a larger climate change trend.

"What oceanographic variable can I tie this to?" she asked. "Pelicans are receptive to or influenced by oceanography."

Pelican counts are a personal project for Jaques these days, something to get her out in the field. She plans to keep tabs on the birds over the next three years and look for patterns in their wintering behavior.

Meanwhile, she predicts this weekend's storm and ensuing chill will drive the pelicans south for the season.

"You would think this would clear them out," she said.

Meanwhile a few miles from home- this isn't a good time for time-share WorldMark. Their brand new place in Long Beach caught fire last night.

Meanwhile a few miles from home- this isn't a good time for time-share WorldMark. Their brand new place in Long Beach caught fire last night.

Coastal Living

Coastal Living